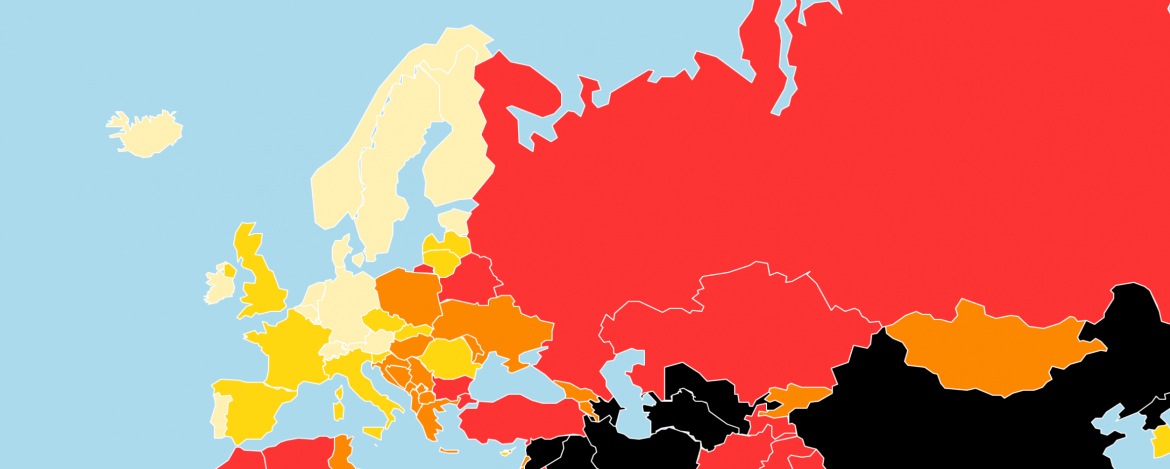

RSF Index 2018: Hatred of journalism threatens democracies

Press release from Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

The 2018 World Press Freedom Index, compiled by Reporters Without Borders (RSF), reflects growing animosity towards journalists. Hostility towards the media, openly encouraged by political leaders, and the efforts of authoritarian regimes to export their vision of journalism pose a threat to democracies.

The climate of hatred is steadily more visible in the Index, which evaluates the level of press freedom in 180 countries each year. Hostility towards the media from political leaders is no longer limited to authoritarian countries such as Turkey (down two at 157th) and Egypt (161st), where “media-phobia” is now so pronounced that journalists are routinely accused of terrorism and all those who don’t offer loyalty are arbitrarily imprisoned.

More and more democratically-elected leaders no longer see the media as part of democracy’s essential underpinning, but as an adversary to which they openly display their aversion. The United States, the country of the First Amendment, has fallen again in the Index under Donald Trump, this time two places to 45th. A media-bashing enthusiast, Trump has referred to reporters “enemies of the people,” the term once used by Joseph Stalin.

The line separating verbal violence from physical violence is dissolving. In the Philippines (down six at 133rd), President Rodrigo Duterte not only constantly insults reporters but has also warned them that they “are not exempted from assassination.” In India (down two at 138th), hate speech targeting journalists is shared and amplified on social networks, often by troll armies in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s pay. In each of these countries, at least four journalists were gunned down in cold blood in the space of a year.

Verbal violence from politicians against the media is also on the rise in Europe, although it is the region that respects press freedom most. In the Czech Republic (down 11 at 34th), President Milos Zeman turned up at a press conference with a fake Kalashnikov inscribed with the words “for journalists.” In Slovakia, (down 10 at 27th), then Prime Minister Robert Fico called journalists “filthy anti-Slovak prostitutes” and “idiotic hyenas.” A Slovak reporter, Ján Kuciak, was shot dead in his home in February 2018, just four months after another European journalist, Daphne Caruana Galizia, was killed by a targeted car-bombing in Malta (down 18 at 65th).

“The unleashing of hatred towards journalists is one of the worst threats to democracies,” RSF secretary-general Christophe Deloire said. “Political leaders who fuel loathing for reporters bear heavy responsibility because they undermine the concept of public debate based on facts instead of propaganda. To dispute the legitimacy of journalism today is to play with extremely dangerous political fire.”

Norway and North Korea, first and last again in 2018

In this year’s Index, Norway is first for the second year running, followed – as it was last year – by Sweden (2nd). Although traditionally respectful of press freedom, the Nordic countries have also been affected by the overall decline. Undermined by a case threatening the confidentiality of a journalist’s sources, Finland (down one at 4th) has fallen for the second year running, surrendering its third place to the Netherlands. At the other end of the Index, North Korea (180th) is still last.

The Index also reflects the growing influence of “strongmen” and rival models. After stifling independent voices at home, Vladimir Putin’s Russia (148th) is extending its propaganda network by means of media outlets such as RT and Sputnik, while Xi Jinping’s China (176th) is exporting its tightly controlled news and information model in Asia. Their relentless suppression of criticism and dissent provides support to other countries near the bottom of the Index such as Vietnam (175th), Turkmenistan (178th) and Azerbaijan (163rd).

When it’s not despots, it’s war that helps turn countries into news and information black holes – countries such as Iraq (down two at 160th), which this year joined those at the very bottom of the Index where the situation is classified as “very bad.” There have never been so many countries that are coloured black on the press freedom map.

Regional indicators worsening

It’s in Europe, the region where press freedom is the safest, that the regional indicator has worsened most this year. Four of this year’s five biggest falls in the Index are those of European countries: Malta (down 18 at 65th), Czech Republic (down 11 at 34th), Serbia (down 10 at 76th) and Slovakia (down 10 at 27th). The European model’s slow erosion is continuing (see our regional analysis: Journalists are murdered in Europe as well).

Ranked second (but more than 10 points worse than Europe), the Americas contain a wide range of situations (see our regional analyses US falls as Canada rises and Mixed performance in Latin America). Violence and impunity continue to feed fear and self-censorship in Central America. Mexico (147th) became the world’s second deadliest country for journalists in 2017, with 11 killed. Thanks to President’s Maduro’s increasingly authoritarian excesses, Venezuela (143rd) dropped six places, the region’s biggest fall. On the other hand, Ecuador (92nd) jumped 13 places, the hemisphere’s greatest rise, because tension between the authorities and privately-owned media abated. In North America, Donald Trump’s USA slipped another two places while Justin Trudeau’s Canada rose four and entered the top 20 at 18th place, a level where the situation is classified as “fairly good.”

Africa came next, with a score that is slightly better than in 2017 but also contained a wide range of internal variation (see our regional analysis The dangers of reporting in Africa). Frequent Internet cuts, especially in Cameroon (129th) and Democratic Republic of Congo (154th), combined with frequent attacks and arrests are the region’s latest forms of censorship. Mauritania (72nd) suffered the region’s biggest fall (17 places) after adopting a law under which blasphemy and apostasy are punishable by death even if the accused repents. But a more promising era for journalists may result from the departure of three of Africa’s most predatory presidents, in Zimbabwe (up two as 126th), Angola (up four at 121st) and Gambia, whose 21-place jump to 122nd was Africa’s biggest.

In the Asia-Pacific region, still ranked fourth in the Index, South Korea jumped 20 places to 43rd, the Index’s second biggest rise, after Moon Jae-In’s election as president turned the page on a bad decade for press freedom. North Asia’s democracies are struggling to defend their models against an all-powerful China that shamelessly exports its methods for silencing all criticism. Cambodia (142nd) seems dangerously inclined to take the same path as China after closing dozens of independent media outlets and plunging ten places, one of the biggest falls in the region (see our regional analysis Asia-Pacific democracies threatened by China’s media control model).

The former Soviet countries and Turkey continue to lead the worldwide decline in press freedom (see our regional analysis Historic decline in press freedom in ex-Soviet states, Turkey). Almost two-thirds of the region’s countries are ranked somewhere near or below the 150th position in the Index and most are continuing to fall. They include Kyrgyzstan (98th), which registered one of the Index’s biggest falls (nine places) after a year with a great deal of harassment of the media including astronomic fines for “insulting the head of state.” In light of such a wretched performance, it is no surprise that the region’s overall indicator is close to reaching that of Middle East/North Africa.

According to the indicators used to measure the year-by-year changes, it is the Middle East/North Africa region that has registered the biggest decline in Media freedom (see our regional analyses Middle East riven by conflicts, political clashes and Journalism sorely tested in North Africa). The continuing wars in Syria (117th) and Yemen (down one at 167th) and the terrorism charges still being used in Egypt (161st), Saudi Arabia (down one at 169th) and Bahrain (down two at 166th) continue to make this the most difficult and dangerous region for journalists to operate.

About the Index

Published annually by RSF since 2002, the World Press Freedom Index measures the level of media freedom in 180 countries, including the level of pluralism, media independence, the environment and self-censorship, the legal framework, transparency, and the quality of the infrastructure that supports the production of news and information. It does not evaluate government policy.

The global indicator and the regional indicators are calculated on the basis of the scores assigned to each country. These country scores are calculated from answers to a questionnaire in 20 languages that is completed by experts around the world, supported by a qualitative analysis. The scores and indicators measure constraints and violations, so the higher the figure, the worse the situation. Because of growing awareness of the Index, it is an extremely useful advocacy tool.

Download the Index and the map:

2018 Index

2018 Map